“As much as I would like to give hope, Kenyan cricket is not in a good state. In fact, the situation is pretty grim.”

Kenyan cricket legend Aasif Karim does not mince his words when describing the current state of the sport in the country.

It is indeed an accurate portrayal with cricket’s popularity in a nosedive and the national board in dire financial straits with historical debts amounting to Sh30 million (US$180,000), which include things like delayed salaries and rent arrears. To make matters worse, ICC maintains tight control over the funding due to the various administrative wrangles and other governance issues that have plagued Cricket Kenya (CK) over the last few years. It has been quite a precipitous fall from the glory days of 2003.

Emerging Cricket sat down with the former captain for an extended interview to discuss his career, that famous spell against Australia and the numerous factors which have led to the downfall of Kenyan cricket.

Sport – A Family Affair

A proud third generation Kenyan Indian, Aasif was born and grew up in the port city of Mombasa. It’s the same city that his grandparents Ahmed and Sharbano Karim had migrated to almost a century earlier in 1926, in search of a better life. The Karims were obsessed with sports and over time the family have etched themselves firmly into Kenyan sporting history.

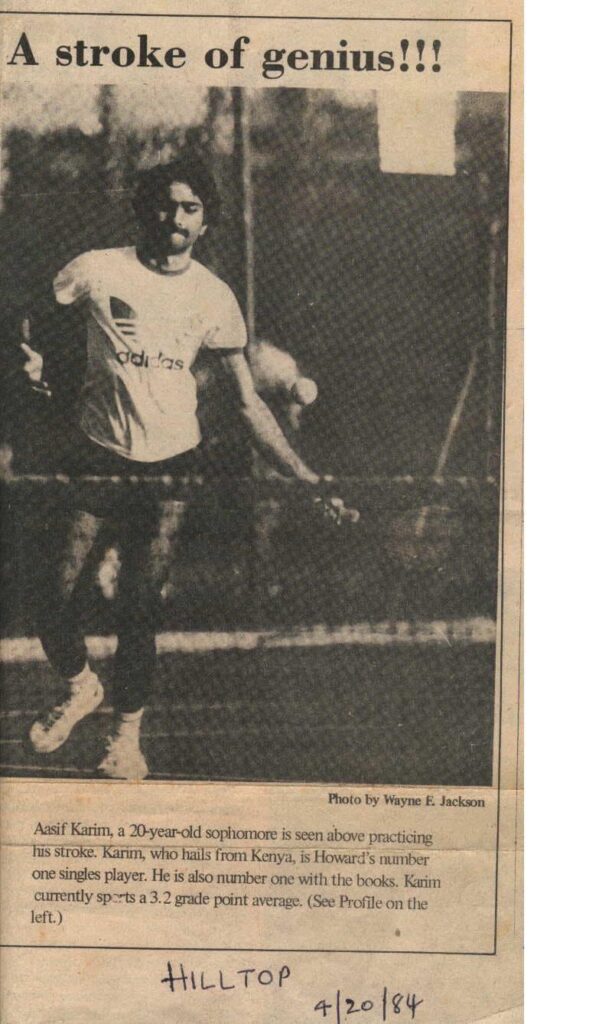

Aasif’s father Yusuf was a highly decorated tennis and cricket player winning multiple trophies and making the sporting headlines. He has a road in Mombasa named after him. Aasif’s older brother Arif also played both sports. And unsurprisingly with Aasif, it was no different.

“Growing up, I played both tennis and cricket. Tennis became very useful to me; it gave me an opportunity to go to the USA and play at the highest level whilst getting my education done. Cricket was not a big deal in Kenya then, it was mainly played at club level. So, you could balance both just fine,” he says.

But in 1992, a major conflict in his playing schedule shifted that delicate balance. “I was playing in the Kenya Open Tennis finals and on that same day I was also supposed to captain my club cricket side in a semi-final. So foolishly, I played both,” he laughs.

The overlaps in his cricketing and tennis calendars quickly became untenable. “Tennis is in some ways tougher because it is an individual sport. After losing the Kenya Cup Final, I was not selected to play for the subsequent Davis Cup fixture against Romania. I was disheartened, I was only 29. So, I made the decision to just stop playing tennis altogether,” laments Aasif.

At the same time, Kenyan cricket was growing up fast. In 1990, it had reached the semi-finals of the ICC Associate Trophy in Netherlands. Four years later, it was hosting the tournament in Nairobi. For Aasif, this meant switching his focus entirely to cricket. “There was a big sense of belief with plenty of young and experienced players in the team; we genuinely thought we had a great chance to qualify for the 1996 World Cup.”

Playing in the 1996 and 1999 World Cups

For the 1996 World Cup, he lost out on the captaincy bid despite being the most senior and experienced player in the squad. Instead, the board chose 26-year-old Maurice Odumbe as captain with Aasif deputising under him. Recalling those days, he is pensive, attributing the decision down to factors other than just cricket.

“Look to be brutally honest, I am living in a country where I am an ethnic minority. There has always been tension between the African Kenyans and Indian Kenyans; ever since the Africans started participating in cricket in the 1980’s. Normally, senior players captain a team but because of the racism and vested interests, I was always vice-captain.”

At the World Cup, Kenya were comprehensively outperformed in most games and finished bottom of Group A. However, they did spring a gigantic surprise against the West Indians, rolling them over for 93 all out chasing a low target of 167. It was a famous victory, one of the greatest and unlikeliest upsets of all time in World Cup cricket.

That ushered in more fixtures against Full Members and arguably the most successful era of Kenyan cricket. In 1997, they received ODI status and Aasif was made captain. He enjoyed the additional responsibilities; handling interviews, fronting up to the media and representing his nation at a global stage. “I had captained my club team regularly, also I had led the team in March 1993 against Zimbabwe for a solitary game. So, I possessed plenty of leadership experience,” he states.

In 1998, Kenya notched another big upset in their tally, knocking over India at Gwalior in the Coca-Cola Triangular Series.

1999 World Cup

Going into the 1999 World Cup, the expectations were high for the Kenyan team to ruffle a few more feathers. Unfortunately, it turned out to be a chastening experience in the cold and swinging English conditions. Kenya lost all five group games, finishing bottom of Group A. With the poor performances and internal board tensions generating negative headlines, Aasif sensed that the time had come to retire from the sport he loved.

“There was so much politics and bickering between the board and the cricketers. And because we did not win a match, the blame comes to the captain. I had the privilege and honour of leading my country at a World Cup in England, the traditional home of cricket.

“I thought I will finish on a high note and retired from cricket before they could sack me. There wasn’t much money in cricket at that time, we were all just playing for the love of the sport, especially the Associates,” he says.

2003 World Cup and that famous spell

Post-retirement, Aasif went back to his day job in insurance. But as fate would have it, cricket was not done with him. Four years later, on the eve of the 2003 ODI World Cup, Aasif received an unlikely call from selectors.

“I always believe in karma, the same administration which had removed me from captaincy begged me to come back. There was a huge crisis in the team in terms of management and leadership, there were threats of mutiny from some players. I must be the only cricketer in the world to have played from one World Cup to another with nothing in between during the four intervening years,” he laughs.

“When I got a call, I was initially skeptical. I had a lot of soul searching to do; it made me wonder if I’m signing up again to go through the same trauma that I did in 1999. But the country needed me and the World Cup is a strong carrot,” he continues further.

And as events transpired, the 2003 World Cup turned out to be an incredible one for Kenya. They made it all the way to the semi-finals, beating a trio of Full Members – Bangladesh, Zimbabwe and Sri Lanka in the process. To date it remains the most successful ICC event for an Associate nation. There were numerous individual memorable performances by the players, but a phenomenal bowling spell by Aasif Karim (8.2-6-7-3) against Australia rightfully grabbed the headlines.

Batting first, Kenya had scored a lowly 174/8 in 50 overs against the defending world champions. And in response the Aussies were cruising at 109/2 in 15 overs, after which fielding restrictions were relaxed allowing five fielders outside the inner circle. Enter 39-year-old Karim.

“As I bowled the first ball, I felt really good. Then second ball I beat Ponting. I asked myself, why do I need to go through the motions here? I am a human being like him, he must get the runs from me. So, I will do the best I can do, there was nothing to lose as by that stage we had already qualified for the semi-finals.

“I kept the pressure on Ponting, every ball he struggled. After I got him out 5th ball, my confidence was sky high. Next over I got the wickets off Darren Lehmann and Brag Hogg, I just went from strength to strength,” he exclaims.

Walking back after the game had finished, Aasif wondered if there was a glitch on the scorecard as it showed six maidens and three wickets for seven runs against his name.

“With all due respect, we are not playing Gibraltar or Israel, we were playing the world champions. I was very proud. I won the Man of the Match award despite us losing and Australia winning by five wickets. When I finished my bowling, umpire Steve Bucknor shook my hands and personally gave me the match ball. I requested Ponting for a signature and he signed the ball for me.”

The Downfall of Kenyan Cricket

After the highs of the 2003 World Cup, Kenyan cricket sadly entered a period of rapid decline. Aasif attributes the downfall to many interrelated factors.

“When you have reached the level we did in the 90s and early 2000s, it is important to sustain it. After all cricketers only have a lifeline of 10-15 years, maybe 20 for the very best; so good players phase out and retire eventually.

“We needed a strong grassroots system from under 11 onwards, so that it can become a successful feeder system in the long run. Unfortunately, we didn’t have that.”

The reality was that Kenya had always relied on a small player pool to generate talent. The sport was played mainly by communal clubs, which in turn were mostly composed of Indian heritage players. According to Aasif, this put a cap on how much success could be translated into increased interest and participation amongst the wider population. “To this day, we don’t have a national cricket ground, everything is membership based. For grassroots development, unless you have the facilities or the clubs supporting it, it will be very difficult.”

Secondly, when the players were becoming semi-professionals, the administration was still being run on a voluntary basis. “We had huge support from Full Members like South Africa and India at that time. Even the ICC were willing to invest in Kenyan cricket, but those funds were misappropriated. We lost a golden opportunity to capitalise on all that goodwill and support.”

Thirdly, Aasif laments that the domestic cricket scene lost quality and became a weak product. “You must have a solid domestic cricket to attract the local community and the businesspeople to keep it buzzing. But with our poor administration, it became a like a pack of dominoes, everything started collapsing one after the other.”

Future of Kenyan Cricket

So, does he see any light at the end of the tunnel for Kenyan cricket? Aasif shakes his head ruefully when asked the question.

“The golden generation of Kenyan cricket that we had during the 1990s and early 2000s, we got lucky. It was a case of the right bunch of cricketers in the same team all peaking at the right time. We can’t keep living in that era,” he states bluntly.

“Back then, we felt like we had graduated to near Full Member level, we were too good to even consider giving Ireland or Netherlands a fixture. Now we are having to qualify for events like the 2023 Africa T20 Cup by playing against Sierra Leone, Cameroon and Mali. Other African nations like Tanzania, Nigeria, Uganda and Namibia are ahead of us in terms of development and participation,” he continues further.

In terms of cricket’s popularity currently, on a scale of 1-10, Aasif assigns a rating of 1. “Football, athletics, rugby and basketball are way ahead. Although in general, the national sporting scene right now is very poor. The only sport we are doing well in is athletics, but those are individual athletes. Even Rugby, which was showing plenty of potential, especially in the sevens format, has similarly collapsed.”

He says that for Kenyan cricket to entertain any hopes of coming back, the board needs to regroup and accept that the cricket scene is at ground zero. “We need competent administration who know how to develop the sport, use the international network to entice quality club cricketers to our domestic scene and build a sustainable programme development wise for the national team.”

Irfan Karim

Aasif’s 31-year-old son Irfan has carried on the family tradition of playing cricket. He has been representing Kenya since making his debut in 2011. With a T20I average of 35 and eight half-centuries, the wicketkeeper-batter is arguably Kenya’s most consistent batter in the line-up at present.

“It’s nice watching my son play cricket. Irfan’s quite talented, he represented England in the University World Cup in 2015 during his studies. He won two Player of the Match awards as well as the best batter award of the tournament.

“You had cricketers like Aiden Markram and Lungi Ngidi playing alongside him. When you see all those guys progressing and your own son representing Kenya, it’s sad to watch because he has been deprived of high-level cricket,” remarks Aasif.

Life Post-Retirement

As an amateur cricketer, Aasif had always been adept at juggling sporting commitments with professional ones throughout his career. Therefore, life post-cricket retirement hasn’t really been all that different for him. “Cricket was never a profession to survive on for myself. I was playing for the love of the sport. We were working all day in our day jobs and then going to net sessions in the evening and on weekends.”

With a keen desire to give back to sports after retirement, he soon started a sports magazine called ‘Sports Monthly’. “I have been religiously publishing that for the last 23-24 years. I write a column for it called the ‘Last Word.’ We cover all sports, although the coverage is primarily focused on domestic Kenyan sports,” he states.

In 2010, an Indian film director produced a documentary on his family, entitled “The Karims – A Sporting Dynasty”, which got featured in various film festivals around the globe. Watching the premiere in India with his wife, Aasif got hooked on films and wanted to start a sports film festival off his own, upon his return to Kenya.

“Kenyan stories can be just as fascinating as all these other ones you know. We have been running this sports film festival for the past six years; we receive over 1200 movie submissions from around 100 countries every year. We run a four-day festival featuring the top sports movies as well as various panel discussions about things affecting sports worldwide.”

In 2017, he became a fellow of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators UK. “I am a private judge and an accredited mediator and that’s what I practice quite a bit now. The magazine and film festival are organised by my foundation,” Aasif clarifies. And he’s still playing cricket, although very occasionally. “Next month in February, I am going to India to participate in the over 60 World Cup. I have been invited to play for the Rest of the World team, I can’t wait!”

You’re reading Emerging Cricket — brought to you by a passionate group of volunteers with a vision for cricket to be a truly global sport, and a mission to inspire passion to grow the game.

Be sure to check out our homepage for all the latest news, please subscribe for regular updates, and follow EC on Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn and YouTube.

Don’t know where to start? Check out our features list, country profiles, and subscribe to our podcast. Support us from US$2 a month — and get exclusive benefits, by becoming an EC Patron.