By Bertus de Jong

Originally pencilled in for May of 2021, England’s historic three-match ODI series of the Netherlands is a year behind schedule, but for the hosts it is a tour that has been well over a century in the coming.

The history of Anglo-Dutch cricketing ties is as old as the game itself in the Netherlands, with cricket in its modern form taking root in Holland in the mid-19th century, borne on a wave of then-fashionable “Anglomania”, and more speculative claims occasionally made that a prototypical version of the game had been exported the other way some much earlier, brought to England from the low countries by Flemish weavers in the early 16th century.

While the game’s lowland origins are a matter of some dispute, the theory based largely on a scrap of doggerel verse attributed to Henry VIII’s tutor John Skelton and some dubious etymological inferences torturing the Dutch phrase “met de krik ketsen” until it yields the word “cricket”, the essential Englishness of the (re)introduction of cricket to the low countries is on firmer historical footing. Indeed the story of at least the first century of cricket in the Netherlands remains inextricable from that of aristocratic Anglophilia, and the borrowed spirit of elitist Corinthianism that would long persist in the Dutch game, eventually to its detriment.

This imported ideal would ensure cricket long remained the preserve of the leisured few in Holland even as equally English sports such as football and hockey were popularised in the country, and English cricket itself underwent its halting and belated demoticisation. The local cricket scene in the Netherlands today may be the model of a multicultural melting-pot, but it owes both its long history and marginal status in Dutch society to an eccentric obsession with all things English that gripped high society across the continent in the mid 19th century, leaving a legacy of somewhat snobbish exclusivity and idealisation of amateurism that would both sustain and constrain Dutch cricket deep into the 20th century.

Yet were it not for those elitist anlgomaniacs there would be no Dutch cricket at all. While versions of the game were not unknown in Holland through the early 19th century, it was first played in its recognisably modern form at Noorthey boarding school (not far from the current international ground at Voorburg) from around 1845. Noorthey’s founder Petrus de Raadt had established the school 25 years earlier in conscious emulation of the English public school model, and despite de Raadt’s own lack of interest in physical exertion the school would soon become a hub for sports of all sorts, as English schoolmasters such as Henry Attwell, G.W. Atkinson and Heldson Rix instructed their young Dutch charges in matters physical and philosophical, all in the fashionable English style.

The game would be spread through the country along with football and hockey by Noorthey alumni such as Pim Muiler, and by the late 19th century there was a thriving club scene among the Anglophile elite. The first adventurous English touring sides would head across the North Sea as early as 1881, eleven of Uxbridge CC, led by Francis Hetherington, making the crossing to administer a drubbing to 22 Dutchmen at the Hague, besting the hosts by an innings and 48 runs in the first known Anglo-Dutch fixture, and returning annually thereafter. The famed patron of the game Henry North Holroyd, 3rd Earl Sheffield, would lead a tour of Holland in 1888, and Sherlock Holmes author Arthur Conan-Doyle would join Norwood CC’s tour two years later. By then the game was well-established in the Netherlands, with the Nederlandse Cricket Bond (it would still be some 75 years before the board earned their royal charter) founded in 1883, being the second oldest (and oldest extant) national cricket board in existence.

In both the spirit and practice of the game (and indeed clarification of the rules) the Dutch board would look across the sea for inspiration and guidance. A series of heavy defeats at the hands of English touring teams would prompt the NCB to take action to improve standards and in 1889, through Rix’s English contacts, they would recruit Arthur Bentley of Newton Abbot for what must surely be the game’s first dedicated overseas coaching role.

The nascent the Dutch board sent the first representative Netherlands team to tour England (well, mostly Yorkshire) in 1892, and two years later, at the invitation of Lord Sheffield, the Dutch would make the crossing again in force. The “Gentlemen of Holland” would make their debut appearance on the hallowed ground of Lord’s in the first game that might be characterised as a representative match between the two countries.

The Dutch team, featuring such names as Friedrich “Top” Rincker, CJ “Kick” Schröder and captained by the great Carstjan Posthuma, would sink to an innings defeat at the hands of a strong MCC side, with the then 47 year-old Rev. Percy Hattersley-Smith and none other than KS Ranjitsinhji both making centuries on a thundery August weekend, before Eton Schoolmaster Charles Allcock ran through the Dutch batting.

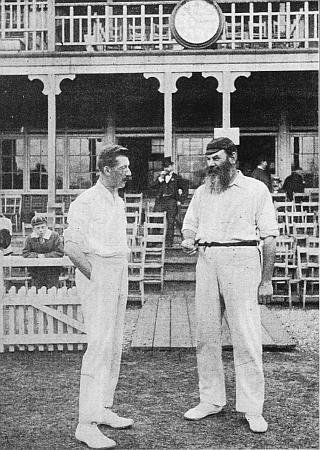

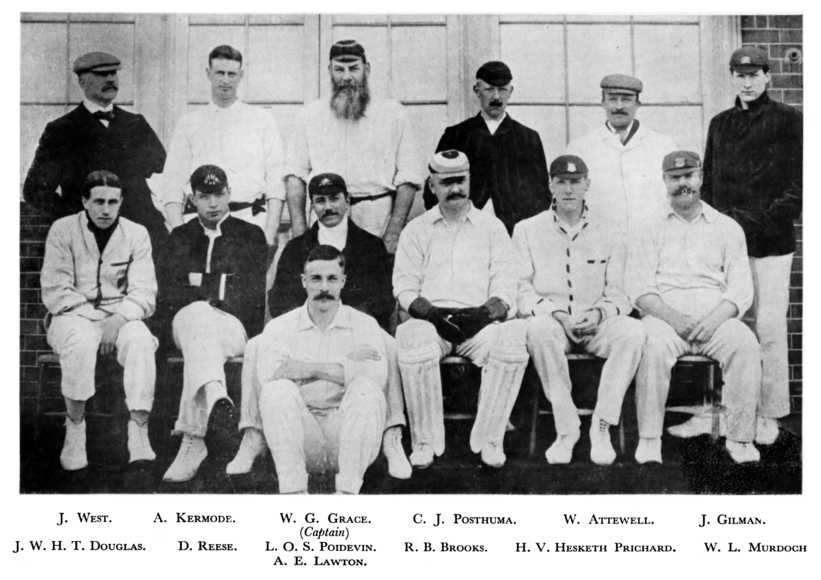

Nonetheless on a return tour by the MCC in 1901 Posthuma’s left arm seam would account for 19 wickets across two matches, and sufficiently impress WG Grace that the grand old doctor invited the Dutch captain to play for London County the following season. Through the early 20th century back-and-forth tours between the Netherlands and England became increasingly commonplace, though Posthuma would remain (excepting Bill Glerum’s one match for the Free Foresters against Oxford University in 1957) the sole Dutch pioneer in first class cricket for the better part of a century.

The first generation of dedicated Dutch cricketers were fated to have their international careers interrupted by the eruption of the Great War, though in neutral Holland the game and its practitioners did not suffer as elsewhere. During the War Posthuma was involved in organising cricket for British servicemen interred after the defeat at Zeebrugge, and the internees would eventually enter three of their own teams into the Dutch competition, the strongest of which was made up almost entirely of former and future First Class cricketers.

Led by Somerset’s Jack MacBrayan and featuring, among others, Gerry Crutchley and Challen Skeet of Middlesex, Gustavus Fowke of Leicestirshire, and future Yorkshire captain Willaim Worsley, Prisoners of War A would win the Dutch Eersteklas competition in 1918. Meanwhile Rincker’s English sympathies would land him in trouble with the law, briefly jailed by the Dutch authorities who found the Anglophile stance de Telegraaf, of which Rincker was editor, threatened the Netherlands’ official neutrality.

The inter-war years would see a renewed flourishing of Anglo-Dutch cricketing ties with the rambling club Free Foresters making the first of what would become regular tours in 1921, and the same year seeing the establishment of the Netherlands’ own touring side, the Flamingos, who would first visit England the following year. English players and coaches too were increasingly sought-after by Dutch clubs who had taken note of the interned British forces skills with the willow, and Haagsche CC’s mid-century can be attributed at least in part to their recruitment of Netherlands national football coach (and occasional Flamingo) Fred Warburton, who would coach the both disciplines at the Hague from the 1920s, building a legacy at the club that would dominate the Dutch league for the next fifty years.

Though the Second World War would of course cut sporting ties between the two countries for the duration, the game would survive the German occupation with the NBC even succeeding in keeping the domestic league running for much of the war. The first match the Dutch would play on liberation would be against a British Army side captained by Brian Valentine, with the hosts winning by 158 runs. Though regular tours resumed almost at once after the war, with the MCC, Free Forester and Flamingo’s all shuttling back and forth with regularity, the first official international between the two countries was still almost half a century off.

While Test sides touring England would regularly stop off in the Netherlands for a game or two before going home – South Africa first visiting in 1951, the West Indies in 1957, and Australia first in 1953 and then famously in 1964 when the Dutch would record their first win over a major nation – the first side to play in Holland in English colours would arrive only in 1989, when Peter Roebuck led a young England XI including Alec Stewart, Nasser Hussain and Derek Pringle to a shock 3-run defeat at Amstelveen, Roebuck’s men would level the series the following day, though by then the headlines had already been written of course.

Hussain would return to the Netherlands four years later leading a side labelled “England” but drawn exclusively from Counties not scheduled to play on that particular July weekend, a situation current Dutch skipper Pieter Seelaar must surely sympathise with. Again the honours were shared in the two-match series, and the tour quickly forgotten. It would prove the last such tour by an unofficial England side, as two years later the Dutch would instead be invited to participate in County one-day competition in their own right. The Netherlands entered a team into the then NatWest Trophy in 1995, though by then Dutchmen were a fairly familiar sight on the county scene, Paul-Jan Bakker the first to establish himself as a regular at Hampshire from 1986, followed by Roland Lefebvre and Andre van Troost at Somerset.

The following year, more than a century after the Gentlemen of Holland first took the field at Lords, the 1996 World Cup would see the first recognised full international between the two sides, England seeing off a spirited Dutch chase to record a 49-run victory at Peshawar. The sides would meet again at the 2003 and 2011 ODI World Cups, with England the victors each time, but in the shortest format the Dutch have had the wood over English in their two encounters on the greatest stage.

Most famously the 2009 World T20 would witness one of the game’s most extraordinary upsets, when the Netherlands again took the field at Lord’s to face the hosts in the tournament curtain-raiser, chasing down 163 on the very last ball in dramatic fashion. Five years later the sides would meet again at Chittagong after the Dutch had hammered their way past Ireland to make the main phase of the tournament, with England at its white ball nadir and the Netherlands flying high the result was barely an upset, England skittled for just 88 as the Dutch sealed a 45-run victory.

For a cricketing culture that has long measured itself against English exemplars, such victories mark a kind of a coming of age for Dutch cricket, slowly shaking off its elitist Anglo-nostalgic roots and belatedly embracing the transformation of both the game as it is played (over limits, coloured kits and all) and the increasing diversity of the community that plays it in the country. Long the only foreign supporters that would habitually cheer for England in neutral games, one is now equally likely to find fans of India or Pakistan dotting Dutch boundaries.

Nonetheless the Netherlands’ own stripey blazers will be out in force again come Wednesday, and while the white and navy blue of Quick Haag or the red and white stripes of Haarlem may look increasingly anachronistic amidst all the Orange – as the Dutch look beyond the legacy of Lord’s to a more modern model of cricket – one could scarcely imagine a more suitable occasion.

You’re reading Emerging Cricket — brought to you by a passionate group of volunteers with a vision for cricket to be a truly global sport, and a mission to inspire passion to grow the game.

Be sure to check out our homepage for all the latest news, please subscribe for regular updates, and follow EC on Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn and YouTube.

Don’t know where to start? Check out our features list, country profiles, and subscribe to our podcast.

Support us from US$2 a month — and get exclusive benefits, by becoming an EC Patron.