The ICC’s eligibility criteria – which determine under what circumstances a player is allowed to represent a given country in international cricket – are among the more contentious regulations governing the game, and especially Associate cricket.

BACKGROUND

There are few lazier cliches about Associate cricket than the derisive portrayals of teams stacked with expats and mercenaries (surely the “plucky amateurs happy to be here” trope is its only serious competition in the hackneyed commentary stakes). It’s a complaint that is often based on little more than a superficial glance at the names on the team sheet – Hong Kong’s men are often victims of this, with the vast majority of the side products of the domestic youth scene despite their largely non-Chinese backgrounds, while Denmark fields a team almost entirely composed of native Danes (some of whom are of subcontinental extraction), but the perception is difficult to shake, largely because there is indeed a kernel of truth to it. Despite frequent commitments from emerging nations to developing “native” players, they are largely drowned out by antics such as Canada replacing homegrown skipper Nitish Kumar with South African ring-in Davy Jacobs, before he’d even played a game for them, or the USA adding Barbados pair Aaron Jones and Hayden Walsh Jr. to their squad mere days after the latter played against them – and controversially ignoring their own selection rules in the process. And just a few weeks ago, recently-capped Proteas offspinner Dane Piedt drew attention to the situation once more as he signed up to join USA cricket’s planned Minor League T20 tournament, with a view to qualifying to play ODIs for the Americans in 3 years time.

THAT WHICH IS – ELIGIBILITY PAST AND PRESENT

As we’ve seen with even high-profile cases like Jofra Archer, the system governing who is allowed to play for which country is the subject of many misinformed opinions in the mainstream press, so for those who don’t keep a copy of the ICC’s player eligibility regulations on their hard drive, it’s worthwhile taking a look at the actual rules.

As it stands, a player can qualify for his or her national team by satisfying any one of the following three criteria – (1) they were born in the country; (2) they are a citizen of the country; (3) they are a resident of the country for three consecutive years. So in the case of Jones and Walsh, both are US passport holders and thus eligible to play (Walsh by virtue of being born on the US Virgin Island of St. Croix).

While admirably intuitive (and, some have suggested, deliberately closer to the Olympic eligibility system), the current regime has certainly been the subject of complaints. Accusations of laxity abound, with the new ease of recruitment said to disincentivise the development of locally-produced players in favour of cutting corners and selecting ready-made players from elsewhere. But if the eligibility changes are smoothing the path for imports, what did the ICC change from? As we know, ring-ins have been a bone of contention within the Associate game for decades.

The previous system did attempt to curb the use of non-local players, with a set of complex restrictions around who could play for Associate nations (though interestingly this standard did not apply to Full Members or the women’s game). The three basic criteria for eligibility – birth, citizenship, residency – were the same (though the minimum time for residency was longer), but there was also an extra layer: paragraph 5.2 (Development Criteria). This was implemented specifically to combat the scourge of expats, as well as so-called “passport players” (citizens of a country with little or no connection to its cricket scene).

For players who met the birth or citizenship requirement to be eligible, they had to fulfil one of three additional criteria – (1) play at least half the matches for a domestic team across at least 3 of the preceding 5 years; (2) spend at least 100 days across the previous 5 years working as a coach, administrator or development officer; (3) have previously represented the national team at U19 level or higher in an official ICC-sanctioned match. Additionally, players qualifying through residence were split into two categories: 7-year residents and 4-year residents. There were no restrictions on 7-year residents, but a team could only field a maximum of two 4-year residents in their playing XI.

So it seems that the ICC was already tilting the scales in favour of locally-produced cricketers (to varying degrees of success). The name “development criteria” certainly indicates an explicit purpose of promoting the game locally. Why the abrupt U-turn then? Has the ICC simply given up trying to resist the mercenary hordes and opened the gate? Well, they still haven’t commented officially, but the most widely-accepted theory is that the change resulted from a challenge to the policy initiated by Philippines Cricket Association.

In February 2017, the ICC held its World Cricket League qualifier for the East Asia Pacific region in Bendigo, Australia. The Philippines squad included several dual-national Filipinos representing their parents’ homeland, two of whom were declared ineligible for failing to meet the development criteria (specifically, Daniel Smith and Henry Tyler). The Philippines appealed to the ICC’s Dispute Resolution Committee, and were handed a surprising victory. In the short term, this simply meant that Smith and Tyler could play. The longer-term result, however, seems to be that the development criteria were legally unenforceable and thus quietly shelved. So if the old system was untenable, what can the ICC do to ensure that the new framework is most conducive to growing the game?

Overall, I think it’s beneficial to first think in general terms about what cricket is hoping to achieve, and then calibrate its eligibility policies to support that. The defunct development criteria were one such attempt. Specifically, they aimed to restrict expats and passport players (in the hope that would incentivise the production of “local” players instead). Notwithstanding the thorny questions of identity, it is here that the chicken-and-egg debate appears though, with the point made by Associates that it’s easier to generate interest with a winning team. The development criteria were also a rather blunt instrument, and one that was not consistently applied. And it would take a hard heart to deny a player like Australian-based Malaysia representative Elsa Hunter the chance to play for her mother’s country, while banning natural-born US citizens Ian Holland, Cameron Gannon and Karima Gore from representing the country sounds legally dubious at best.

Additionally, the ICC’s funding model for Associates has until recently included onfield performance as a criteria, with the senior men’s ranking counting for over a third of their scorecard weighting. With a few ranking positions making potentially hundreds of thousands of dollars difference, Associates were understandably desperate to field the strongest possible team.

WHERE CRICKET STANDS

This incentive to pick the best team is hardly new, nor indeed is it restricted to cricket. Back in 2007, then-FIFA president Sepp Blatter was making grim predictions about weaker footballing nations bolstering their national sides with imports from Brazil: “If we don’t stop this farce, if we don’t take care about the invaders from Brazil towards Europe, Asia and Africa then, in the 2014 or the 2018 World Cup, out of the 32 teams you will have 16 full of Brazilian players.” Seasoned observers of Associate cricket will recognise the hyberbolic complaint all too well, but it speaks to a challenge facing most international sport – that globalisation and multiculturalism have made national identities significantly more fluid, and regulations around who counts as a national team player more complex. As such, it is instructive to briefly compare cricket’s rules with other sports.

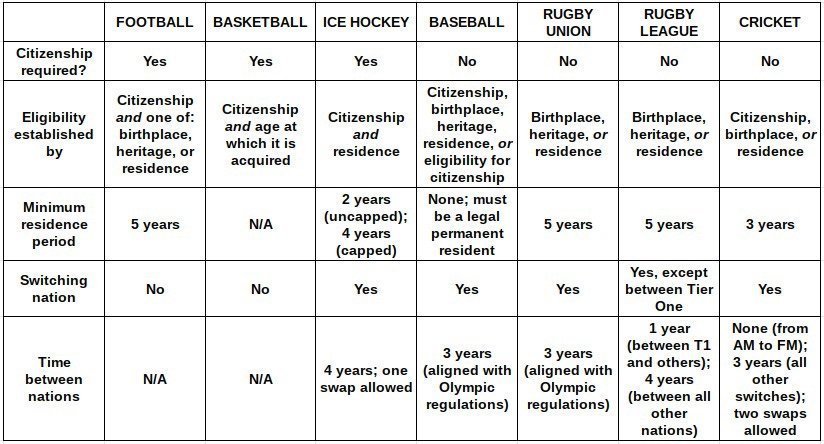

FIFA’s response to the “invaders” was simple – boost the residency requirement for a change of nationality from 2 to 5 years. Thus naturalised players without an established familial connection to their new nations had to wait significantly longer, shifting the calculus for athletes whose careers have a limited timeframe. One notable difference with cricket, however, is that football does not (in general) allow players to switch teams once they have represented a nation at senior level. This has resulted in numerous cases of young players who are eligible to represent multiple nations being approached by one (or both) to commit early and prevent them “getting away”. Basketball is another sport where players are usually not allowed to swap nations, and eligibility is even stricter. FIBA only allows legal citizens to represent a country, and each national team is only allowed to field a single player who acquired their nationality after the age of 16 (applying to both naturalised citizens and so-called “passport players”).

Meanwhile, both codes of international rugby allow players to switch allegiances, though with various stand-down periods, and in the case of rugby union, tied to the Olympic qualification pathway. Union has also recently upped its residency qualification from 3 years to 5. Baseball has perhaps the most relaxed eligibility rules, with players allowed to compete for a national team if they are a permanent resident, a citizen, the child of a citizen, or eligible for citizenship of that country. Thus Israel has assembled a strong national team from Jewish-American baseballers (to similar complaints by disgruntled opponents as are no doubt familiar to the UAE cricketers). Ice hockey is another sport which allows players to change eligibility, though players must be a citizen of their new country and have played in its domestic league for either 2 or 4 years (depending on whether they have previously been selected at international level).

So what does this all mean? It is worth noting that the different approaches across international sport reflect each sport’s unique priorities and position. Football’s strict anti-import rule and hardline approach to nation-swapping is relevant as a result of the sport’s dominant place in the international spotlight; trophy-hungry national governments paying to fast-track citizenship for athletes is significantly less of a concern for, say, rugby league. That code, and baseball, both recognise the lopsided nature of their international scenes – a few highly-developed countries are miles ahead of the rest, where the sport is a relatively niche interest. As such, they calibrate eligibility with an eye to promoting the sport, aiming to somewhat level the standard and make international (especially tournament) play a more appealing product to viewers. Cricket, with its high level of stratification between a few haves and many have-nots, falls firmly in the latter category.

As such, the nuanced approach of rugby league to eligibility is the most relevant comparison. League’s eligibility criteria are fairly standard in the sense that the connection to a nation is established through birthplace, heritage (parents or grandparents), or residency (5 years). Where the sport differs, however, is in dealing with players who qualify for multiple nations. Under the criteria there is an explicit distinction made between the so-called Tier One nations where the sport is popular (Australia, England and New Zealand), and the rest of the world, where the sport is attempting to grow. So while players may only ever play for a single Tier One nation, they can switch freely between it and any other single nation they qualify for, with the only restrictions being that they can only play for one team in any calendar year, and they can’t switch during a global event. For players eligible to represent multiple nations that aren’t Tier One, there is a 4-year waiting period for each switch.

CONCLUSION – THAT WHICH OUGHT TO BE

Comparatively speaking, cricket is about the middle of the pack in terms of eligibility criteria. It is however relatively relaxed about switching allegiances, and moving to the 3-year residential qualifying period seems to go against the trend of other sports looking to tighten residency rules. If we accept the premise that the eligibility criteria should reflect both the current realities of the sport, and where the sport aspires to be, I believe that Rugby League’s model is one that cricket would do well to learn from.

Cricket’s eligibility already contains some recognition of the unique dynamics between stronger and weaker nations, with the 3-year standing down period between nations waived if a player moves from an Associate Member to a Full Member. This makes sense, because without such an exemption, it would incentivise talented AM players to retire prematurely (or even decline selection altogether) from their native country in order to pursue a more lucrative and prestigious career in an FM setup. A team like Scotland would be severely affected, with a large contingent of their first-choice players on county contracts which mightn’t be offered were they not England-eligible. Conversely, swapping between two Associates or two Full Members requires a waiting period as there is less of a power imbalance between the two; weaker FMs like Zimbabwe and Ireland could plausibly argue to be affected by the same factors, however, so cricket could perhaps consider the rugby league system of tiers for eligibility purposes.

Where cricket differs significantly, however, is in going the other way (i.e. from a Full Member to an Associate Member). This is illustrated by the case of Ed Joyce, who needed to apply for special dispensation to play for his native Ireland in the 2011 World Cup, after being discarded by England following the 2007 edition. The current waiting period means that once an AM player is selected, no matter how briefly, by an FM side, they must wait 3 years before they can play for their AM side again. If cricket wants to raise the standard of the game, depriving Associates of years of service from their top players seems unfair, and I think we should seriously consider the way rugby league makes it as easy as possible for players from emerging nations to continue representing them.

Regarding “passport” or heritage players, it must be stressed that cricket is not an outlier. Many teams in many sports select many players who qualify via ancestry, and in an increasingly multicultural and globalised world, it seems futile trying to parse out which citizens of a country “really count” as being allowed to play for their national team. The case of Kevin and Jerome Boateng highlights this in football, with both born and raised in Germany, but one playing for that nation and the other for Ghana (their father’s birthplace).

Where cricket is more relaxed than several other sports is eligibility of resident non-citizens, and this is where I believe there is room for the rules to be brought more in line with development priorities. As the example of Dane Piedt has highlighted, a 3-year waiting period is seemingly not seen as much of an obstacle to recruiting a fringe player with Full Member experience but no connection to the local scene. Increasing the residence requirement seems like a proportionate step to help weed out cases like Piedt (foreign players whose careers may be winding down), and to raise the costs of sponsoring a player to wait out a qualification period. Some concessions may be necessary for players who move with family or before they turn 18.

Overall though, it’s refreshing to find that cricket’s eligibility regime is actually relatively sound. It is largely in line with international sporting standards, and with a few tweaks to more dynamically respond to the unique needs of the sport, could easily be close to best-practice. If only the ICC were more transparent about their decisions on the topic.

Keep up with the emerging game through our Facebook and Twitter pages.

Looking for audio content on the emerging game? Add the Emerging Cricket Podcast to your favourites on Apple, Spotify and Podbean.

Want extra Emerging Cricket content? Contribute to the Emerging Cricket Patreon cause from as little as $2 a month. Sign up here!