This article serves as a rebuttal of the argument justifying the ICC’s decision to reduce the CWC to 10 teams on the basis that including more lower-ranked teams leads to predictable mismatches.

This is a condensed version of the long-form “Of Upsets and Unpredictability: an in-depth analysis of ODI competitiveness“.

THE CLAIM

Broadly speaking, the 10-team format is justified on the grounds that a more inclusive tournament dilutes its quality, with one-sided drubbings of Associates getting in the way of more exciting cricket. Thus, restricting entry to the very best guarantees competitive matches.

The ICC (through its CEO David Richardson who finishes up in the role at the 2019 World Cup’s end) made their stance clear in numerous interviews, the most poignant was in 2015 just prior to the 14-team (and arguably most successful ever) CWC when asked why four sides were being removed from the sport’s pinnacle event.

“Every match should be very competitive. Having 10 teams at the 2019 World Cup will make sure that will be the case”

David Richardson – ICC CEO, 2015

THE RESPONSE

I’ve written extensively against the notion that top teams are any guarantee of close matches, and I stand by my conclusion that the thrashings handed out to Associate Members are not greatly more than Full Members thrash each other (and indeed, since the 2015 World Cup, matches between Full Members and Associates are significantly less likely to result in a blowout than matches between Full Members only as I set out using a basic run/wicket criteria).

However, margin of victory is not the whole story of competitiveness. Often when confronted with the reality that most FM-FM matches are one-sided, the anti-Associate argument shifts the goalposts to claim that AMs are actually uncompetitive because they “usually still lose”, while we don’t necessarily know which FM will thump which on any given day; basically the problem is not with one-sided matches per se, it’s merely that Associates don’t win enough of them.

The other relevant factor is that of rankings. With top AMs closing the gap to weaker FMs (to the point where it barely exists anymore), the relative position of teams on the rankings table becomes a more accurate predictor of the likely outcome than membership status.

once teams go beyond 4 ranking places of each other, the competitiveness falls off a cliff

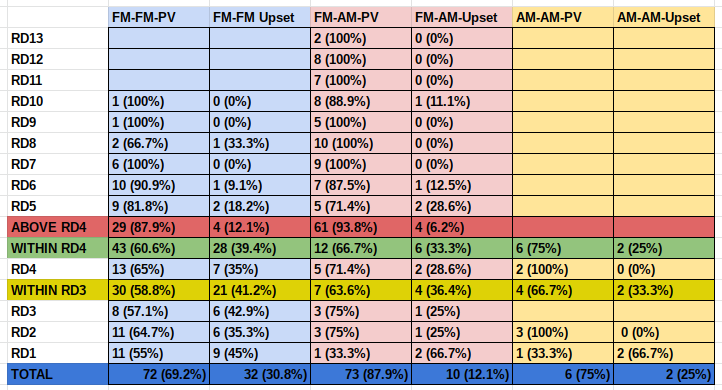

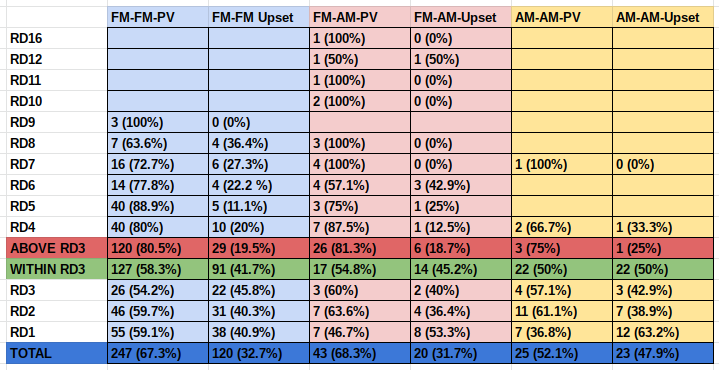

To that end, I’ve examined the effect of ranking differences on expected results, comparing the number of upsets (i.e. lower-ranked teams beating or tying with higher-ranked opponents) between AMs and FMs, as well as in FM-only matches. In line with my previous piece on margins of victory, I’ve taken data from the 2003-2015 CWCs as a cutoff, and I also tallied up the results of ODIs in the 4 years between the last world cup and CWC19 (but including the Netherlands’ series win over Zimbabwe) in order to get a more in-depth picture of the current state of competitiveness.

THE NUMBERS

As expected, the highest chance of upsets occur between the teams ranked closest together, and the bigger the gap in rankings, the lower the chance of an underdog victory. It was not, however, a linear scale, with the chances of an upset holding steady for closely-matched teams then dropping sharply above a ranking difference (RD) of 3 or 4. In the CWC data, Full Members within RD3 and RD4 pulled off upsets at a rate of 41% and 39% respectively. Associates were broadly comparable, and only slightly less successful with 36% and 33% within the same RD. But once teams go beyond 4 ranking places of each other, the competitiveness falls off a cliff – FMs had a miserable 88% chance of losing to higher-ranked opponents while Associates lived up to the negative hype with a truly dire loss percentage of 94%.

The post-2015 data indicates that the trend towards stratification has become further entrenched, with the drop-off point in results just 3 ranking places. Within RD1-3, FM matches are quite unpredictable with a respectable 42% chance of upsets. After that, though, it falls by more than half to just 19.5%. Associates, meanwhile, were actually more competitive with closely-ranked teams, scoring upsets over FMs in 45% of matches within RD3. For RD4 and above they performed only fractionally worse than their FM counterparts with an upset chance of 18.7%.

THE CONCLUSION

Several inferences can be drawn from the data. Firstly, that ranking difference is a much more accurate predictor of results than membership status, with Associates having virtually eliminated the gap between themselves and the low-ranked Full Members. Secondly, that the gulf between top-ranked FMs and the rest of the pack is widening – as is borne out in the results of the current CWC, with semi-finalists mostly decided with over 2 weeks left of the group stage; and although England’s perennial ability to disappoint their fans has opened up the last semi-final place, relying on the #1 team forgetting how to play is a risky means of generating tension in a format. Further, the band of competitiveness (within 3 or 4 ranking places) is so narrow that any multi-team event is almost certain to suffer from predictable mismatches; that is to say, like one-sided margins of victory, predictable outcomes are simply part of cricket (and indeed all sport).

So what does that all mean for cricket’s flagship event? The most obvious conclusion is that a 10-team league format is not the panacea to “uncompetitive matches” plaguing the game, with 21/45 group matches played between teams ranked more than 3 places apart (and thus highly predictable). It also means that, short of a farcical quadrangular “World Cup”, the simplistic answer of cutting more teams is not fit for purpose.

Rather, the way forward is through better scheduling and format design. Playing multiple games (and especially likely mismatches) on the same day would increase the chances of one being exciting, while a fast-paced group stage could get the inevitable “predictable” matches out of the way quickly, with weaker teams sent home early, and prioritise excitement-building knockout matches. A more cutthroat tournament would also do wonders for the interest, and by clearing the dead wood early, it sets the stage for punchier encounters between the better (and presumably more closely-ranked) sides – rather than fizzling out into a fortnight of dead rubbers by keeping the worst teams involved until the bitter end.