Whereas Part 1 charted the history of the Thailand women’s long road to World Cup qualification, in this article we talk in-depth about the Thai players’ motivations, and the various elements that have contributed to their success in recent years. We dissect pressure moments in the T20 World Cup Qualifier and touch upon the team’s preparations for the ‘Big Dance’.

The Sports Authority of Thailand (SAT) is a twenty-eight-storey edifice in the Bangkok suburb of Ramkhamhaeng. Nearby is the equally imposing Rajamangala Stadium, home to the famed ‘War Elephants’, Thailand’s national men’s football team. Both structures are artifacts of Thailand’s status as a powerhouse of South East Asian sport.

Of course, the success of Thai women’s national cricket team has eclipsed South East Asia and indeed the continent. It has been a month since Thailand’s clinical win over the PNG in the ICC Women’s T20 World Cup Qualifier paved the way for a spot in the T20 World Cup to be held in Australia.

But their international success is too new for swanky administrative buildings, or big stadiums. Cricket still remains a boutique and largely amateur sport in the country.

The head office of the Cricket Association of Thailand (‘the Association’) does sit inside the SAT, but you wouldn’t know it. The office is small and self-contained, tucked away in a corner of one of those maze-like floors in the building. I remind myself that cricket in Thailand was not even recognized by the SAT in the mid noughties. That the Association is even hosted at the SAT today as a testament to how far they have come.

At the entrance to the office is a life-size congratulatory poster of the women’s team’s remarkable world cup qualification. I enter the small open-plan office to more of the same. There are pictures, posters, and other forms of paraphernalia everywhere. The Association evidently takes great pride in the exploits of its women’s team and they are keen to talk about it.

So Emerging Cricket is in Bangkok to interview Sornnarin Tippoch, Naruemol Chaiwai, Suleeporn Laomi and Shan Kader.

Introductions to the sport

I begin by asking the players how they started playing cricket in a country where very few Thais knew anything about it ten years ago.

Captain Tippoch was a university-level softball player. The Association was conducting open trials for the first women’s national cricket team at the time, and it was Tippoch’s university coach who suggested she try the sport. “I knew nothing about cricket, but that was what made it interesting. I was curious and also wanted to challenge myself. I had no idea that I would get this far,” she says, grinning.

It is a day before the three players get on a plane to Sydney. They are part of the Women’s Global Development Squad, which will tour Australia and play matches against the Melbourne Renegades, the Melbourne Stars, the Adelaide Strikers, and the Hobart Hurricanes. They have come far.

Chaiwai also started out as a softball player, albeit at the school level. She appeared at open trials for the U-19 national team, and was appointed Captain for the ACC U-19 Women’s Championship 2008. The team finished second in Group A and lost comprehensively to Nepal in the semi-finals. Chaiwai thought, what she saw as an adventure, was over.

“Then I got a call from the Association to say there was a senior women’s tournament happening in Malaysia. So I thought, ‘why not challenge myself further?’ I got on board and I am still learning so much about the sport today.”

Kader, who is the team’s manager, challenges what he calls the ‘transitional sport narrative.’ In the early days softball, hockey and even sepak takraw were all sports from which young Thai female players transitioned into cricket. Players joined the team with high levels of physical fitness and core skills such as hand-eye coordination, all of which eased the transition. “But we quickly realized that such an approach would not build a sustainable women’s program. We needed to nurture talent from a young age,” he says.

Suleeporn Laomi is the poster-girl for this grassroots development program. Laomi was a track and field athlete until the third grade. Kader and another coach spotted her at an open trial when she was ten. “We saw her bowl one ball seam-up and stopped her right there. From that moment on she has bowled leg-spin, and here she is today.”

Gone are the days of open trials for national teams. Kader now oversees a pool of more than fifty advanced, intermediate, and beginner coaches around the country. They are based around the country, and are tasked with identifying talent and recruiting players for provincial teams. In Laomi’s early days, cricket was only played in four provinces. Today it is played in fourteen, at the senior, U-19 and U-16 levels.

Kader and the other high performance coaches also scout players at domestic tournaments such as the National Games, held every 2 years in towns across the country, and funded entirely by the SAT. The most talented players at these tournaments are invited to the one of three Centres of Excellence for cricket, located in Doi Saket (near Chiang Mai in the North), Rattanakosin (an area of Bangkok), and Chanthaburi (near the Cambodian border in the East). Schools partner with the Association to host the Centres. The Association builds outdoor and/or indoor nets, provides equipment and places specialist residential coaches, often current or ex-national players at each school. In turn, players are offered a place at the school, a bunk in the dormitories, and free meals. Laomi, for example, attended the Centre in Doi Saket, which attracts many other talented cricketers from hill-tribe backgrounds.

This program is one key foundation of success for the Thai national women’s team. Kader is quick to tell me that there are many talented players coming through the pipeline. As I write, the U-19s have just won the inaugural Belt and Road Tournament against Nepal, Malaysia, China, and Myanmar.

Want to read more articles like this? Click on the button to help us!

Committing to a bigger goal

Introducing girls and boys to cricket is one challenge, retaining the good ones is another. Yet longevity, stability, and the accumulation of varied international experience have been hallmarks of the Thai women’s upward trajectory in the associate cricket world. This world is an overwhelmingly amateur environment where individuals ultimately have to choose between livelihoods and sport, especially in the women’s game. Add to this the fact that the sport has limited profile in Thailand, and that, in Tippoch’s words, “you have to be twice as tough [as a woman] because you are doubly scrutinized for everything that you do,” at home and in the community.

I ask the players what motivated them to keep playing cricket in Thailand more than a decade before they could seriously entertain thoughts of playing in a World Cup.

Tippoch, Chaiwai, and Laomi say that they have and continue to be motivated by the reality of representing and winning matches for their country, and increasingly real prospect of making a steady living from the sport. “It was my dream as a child to represent my country as a sports athlete and this was an opportunity to wear the national colours,” says Tippoch. It is a responsibility she takes extremely seriously, evidenced by the intensity with which her side competes, but also by the fact that the players view themselves as ambassadors for the country.

Two examples of the latter stand out. The day after Thailand’s last monarch died in 2017, Tippoch spoke to the South China Morning Post (SCMP) before a crucial World Cup qualifier against Nepal. “We have lost everything, but today we try to beat them because we play for our king, my king. We have nothing to lose because we play for our king.” Then there is the customary team ‘wai’ at every game. “We want to show people our traditions, but is not for show. It is what we have been doing since day one. Win or lose, we do it. It is just a very nice traditional gesture that shows what a Thai person is and our values.”

Chaiwai also talks passionately about “just wanting to wear the national colours,” but concedes that the decision to pursue the sport professionally was a challenging one to make. Chaiwai’s grades dropped dramatically when she started playing, creating self-doubt and anxiety about the prospect of being able to balance her studies in Chiang Mai with training in Bangkok and travel overseas.

“I went from being a class topper to being at the bottom. My mother advised me to stop playing. I kept asking myself whether I should do this and whether it would simply be too difficult. The real turning point was when I represented the U-19s and got a tournament fee of THB 10,000 (US$332). I gave it to mum and we both realised that there may be an opportunity to make a living representing the country.”

Laomi had a rare, early taste of professional cricket in the most glamorous of environments, the Women’s Big Bash League (WBBL) and was hooked.

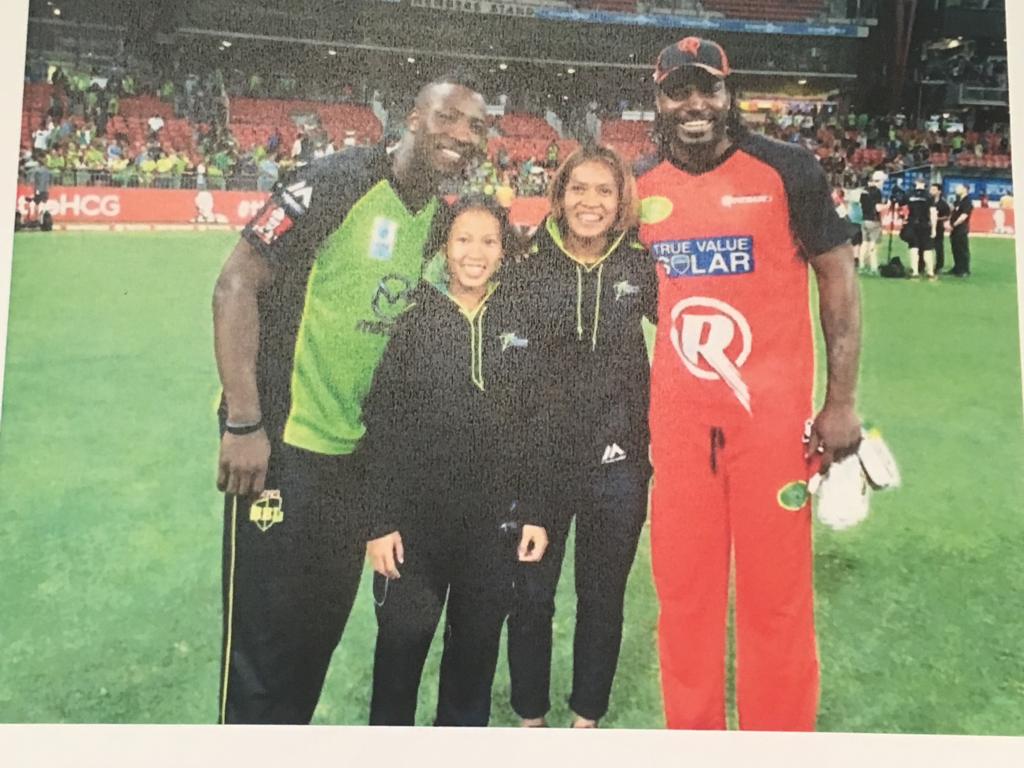

“I was part of the Sydney Thunder [as an Associate Rookie in 2015]. At first I had no idea who all of these players were. Additionally, I could not write English so had to write their names down phonetically in Thai, and memorize them. I took all of these photos with Stefanie Taylor, Alex Blackwell, Andre Russell, Chris Gayle and others. Then I saw them on TV and had an ‘OH MY GOD’ moment. But it was really when I saw Meg Lanning playing on TV around that time that I decided I wanted to be like her and go to a World Cup.”

There are factors extrinsic to the players’ goals and motivations that have enabled longevity in the national women’s set-up. The Centre of Excellence program is one way in which the Association has kept talented players in the game and fostered their improvement over a decade. There are others.

All sixteen national squad players live together in one house in Bangkok. Whilst this, they say, can be excruciatingly claustrophobic, it has immense benefits. According to Kader, “living creates a kind of contagion. They are drawn into each other’s interests and activities, and also understand each other’s personalities much more intimately than other groups of sporting teammates. As a result, we are acutely conscious of our common purpose, and gel as a family.We had a bond on the field in Scotland, which a lot of teams did not.”

What appears to be a strong and healthy relationship between staff and players also generates a unique level of awareness and responsiveness to individual pressures and needs. Given that the Association cannot give players full-time contracts without also employing them, some have to study or work elsewhere. Players are able to negotiate their schedules and routines with the managers and coaches, depending on commitments such as university exams, whilst also training at a level required to compete with the top emerging cricket nations. Laomi is currently juggling cricket with a university degree in physical education. There are times when she travels up and down to Chiang Mai (twelve hours by train from Bangkok one way) every week so that she can meet her university requirements whilst also training. Sometimes she has to train on her own in Doi Saket, and the Association trusts her to do so.

The Association’s response to Tippoch’s post-university dilemma is also instructive.

“I started a bit later than everybody else. I was twenty-one when I first started playing cricket and it was the point in time when I was about to finish university. I had to ask myself whether I could really take cricket seriously or whether I just had to go out and find a job to pay the bills.”

The Association realised this and quickly stepped in, offering Sornnarin a job to come on board as a coach. This offer solved Sornnarin’s financial concerns but also allowed her to work in her preferred field (sports science).

Of course, the team’s timely on-field successes have also played a role justifying further investment in individual players, and in creating a collective confidence in the overall project. In 2010, the Thailand women’s team finished second last in at an ACC U-19 tournament in Singapore. It was Laomi’s first tournament. Two years later, Laomi captained the U-19 team in Kuwait and they finished second. “There were obviously big steps of improvement along the way, and this reaffirmed our belief in the team and the project,” says Kader. These wins have come time and time again.

Winning the gold medal at the South East Asian (SEA) games in 2017 was a different kind of pivotal moment for the players, the Association, and the sport alike. A SEA games medal meant a lot more to the Thai population than World Cup Qualification. National media covered the achievement. Banners heralding the team’s success popped up at players’ universities and schools. Some players were paraded through their hometowns and villages. The SAT rewarded each player THB 200,000 ($AUD 9,700). This despite the fact that most well-wishers had no real knowledge of the sport itself.

According to Kader, the adulation and support the players received after the SEA games solidified the idea that “there is real potential in cricket, not just with medals, but possibly through opportunities in the international T20 leagues as well.”

Planning and playing like professionals

Participation in the WBBL or the Kia Super League will come from success and recognition at the World Cup. In order to qualify in the first place, the players have had to harness and translate their collective commitment into the performances we saw in Scotland.

According to Kader, 2013 was a turning point. The team made it to the global qualifier and, as Kader says, “had to address the challenge of raising its game to the next level. We realized very quickly that we did not have the high performance program to take them there.” As outlined in Part 1, the Association has since invested heavily in pre-tournament exposure tours, specialist foreign coaches, and closed camps.

But as I learn, since 2018, Thailand has prepared harder and more strategically than ever before. Harshal Pathak has been a key factor in this step up. Pathak is a meticulous strategist and planner. “He even knows which foot each player should step out the door with every morning,” says Tippoch, chuckling. The level of attention devoted to each individual is astounding for a largely amateur team.

“Every player in the squad has a weekly and monthly plan with clear targets for what is to be achieved in physical fitness, skill development, and game awareness. There is no such thing as a mere group training session. Every time we train, we are individually challenged to achieve something specific, both physically and mentally. We have to meet actual targets, consider how to achieve them, figure out what we need to go back and work on, and then write it down in our diaries. Sometimes there’s too much going on and our diaries help us focus.”

The players are expected to train like professional athletes and have evidently embraced the transformation.

I note the calmness that the team appeared to exude in high-pressure situations in Scotland, and the ability to orchestrate victories from difficult situations, including against Namibia and Ireland in the group stages. I ask whether and how they have prepared specifically to execute their skills in such scenarios.

“Well, of course, we planned for scenarios such as these,” says Kader.

“Harshal knew that rain would be a factor in Scotland [as it was in the shortened Ireland game] so we trained to achieve batting targets, fine-tune bowling plans, and set fields for these kinds of scenarios. We covered 5-over, 7-over, and 10-over games. We even encountered a super-over in a practice game in Pondicherry. This intentionality in planning gave us real experience and clarity about what needed to be done if we encountered similar situations in the tournament.”

Pathak’s introduction of yoga into the team’s regime over the last year or so has instilled a level of clarity, and calmness in pressure situations. It has helped the players become more self-aware and focused in the field.

“In the Ireland game, a lot of people rightly thought we would be more flustered and fidgety, but the combination of preparing ourselves for these high pressure situations and the greater levels of mental discipline gained through yoga helped us immensely.”

As if to explain how these factors translated on the field, Tippoch breaks down her mindset going in to bat with the score on 6/37 against Namibia. “Yes there was pressure, but I knew my target and my plan. We calculated that if we scored 80 runs on that wicket, we would likely be able to defend it. I trust our bowling unit that much. I also knew I had a solid partner in Wongpaka Liengprasert, who also understood the plan. So we just had to absorb the pressure, keep pushing, and stick to the target.”

Kader also highlights the players’ ability to read the game and make sound tactical decisions on their feet as another important factor in these close wins. In their first tournaments, some of the players did not understand the intricacies of the game. They would bowl when told to bowl, and field where they were asked to field. That was the extent of their involvement in the game. Today, each ball is a tactical battle and everyone generally knows their specific role in that particular moment. Tippoch, in particular, comes in for strong praise. “The Ireland game was challenging tactically because it was a shortened fixture and the bowlers had to be rotated in a precise manner, such that we had enough runs to play with in the last over. Noi’s [Tippoch] decision to bowl Chanida earlier was crucial because she took the wicket of the in-form left hander and left us around eight runs to play with in the final over. Then it was just a matter of putting key fields in particular boundary slots, and strangling them in the circle. She [Tippoch] handled it really well, as we expect her to.”

Equally important was the fact that the Thais knew exactly who they were playing at the tournament and how to approach each opponent. One of the key reasons for the preparatory tour to the Netherlands was to gain insights into the two teams perceived to pose the biggest obstacles to world cup qualification: Ireland and Scotland. Kader is unequivocal. “We knew exactly what their batting line-ups look like, who bowls what, which bowler to go after, and what a good total against them would be.” These one-percenters helped immeasurably in close games such as the one against Ireland.

“I don’t think any team would have dialled it [their preparation] down to that level of detail. We did and it paid off.”

***

World Cup qualification has spurred the Association, the staff, and the players into further feverish action. This is not a project that pauses. Everyone is acutely aware that the quality of cricket in Australia will be two notches above what the team encountered in Scotland. They are not travelling to make up the numbers.

The team is clear about its goal and the way in which it will approach the tournament. The tone is certainly not one of pie-in-the-sky bullishness, but it is also far from defeatist. “There’s no pressure. We have nothing to lose. The eyes of the world will be on us. We will go there and do our best,” says Tippoch.

“We want to finish in the top eight so that we do not have to go back to the Qualifiers for the next world cup,” Chaiwai reveals. Kader chimes in with a word on how this might be achieved. “We know which team(s) we are going to target in our group and we think we have got a chance.”

The focus before Australia is to diversify the bowling attack and become accustomed to playing length and short bowling at a quicker pace. In order to accomplish this, there is a preparatory program already in place. The team’s main batters have been in Pune for over a month, facing young, male pace bowlers, and honing their skills against bowling machines. The team will then travel to Australia to play against a number of state sides, before heading back to Asia for a month to finalise preparations and pick their final squad.

The Association is already looking ahead to the 2020 50-Over Women’s Cricket World Cup Qualifier in Sri Lanka. Rather ambitiously, it plans to bring a number of Test teams to Bangkok for a 50-Over version of the ‘Thailand Smash’ in April 2020.

It sounds somewhat grandiose until I remember again that all three players sitting before me are off to Australia tomorrow to play against some of the best women’s players in the world. I glance once more at the poster heralding the team’s qualification for the T20 World Cup. I once again remind myself that ten years ago, the Association’s head offices lay tucked away in a nondescript area of Bangkok’s urban sprawl. Today they are in the SAT, the home of Thai sport.

I pause to take it all in before thanking the Tippoch, Chaiwai, Laomi, and Kader for their time. We agree to meet in Australia, hopefully over a bowl of noodles after an upset or two.

Keep up with news and events from cricket’s new world on Facebook and Twitter pages.

Looking for audio content on the emerging game? Add the Emerging Cricket Podcast to your favourites on Apple, Spotify and Podbean.

Great article.

Enjoyed reading your article